Considered by many to be one of the most remarkable women of the twentieth century, Leni Riefenstahl was an accomplished artist, dancer, actress, photographer, cinematographer, script-writer, technical innovator, mountaineer, skier and of course, director. The brilliance of her 1935 film Triumph of the Will is remembered as much for its artistry as it is for its political controversy. However, Leni’s intimacy with National Socialism should not distract from her work and vision, at least no more so than Mikhail Kalatozov’s or Sergei Eisenstein’s political affiliations distract from theirs. Leni was once referred to as the epitome of the perfect German woman in mind, body and spirit; indeed, there is a strong visual language of Teutonic archetypes permeating through her repertoire spanning over seventy years. Leni’s career began in Weimar Germany where she, a graduate of the prestigious Grim-Reiter Dance School, made a name for herself as a successful dancer. Her profession carried a physical toll and she was recovering from various injuries when she first saw a poster of Arnold Fanck’s Mountain of Destiny (1924). The bergfilm captured Leni’s attention and inspired her to enter the film industry. Her good looks, screen presence and sheer athleticism proved to be a perfect match for the genre; she would go on to star in Fanck’s iconic 1926 film The Holy Mountain, that established her as a star in Germany and presented an ideal of German femininity to the rest of the world.

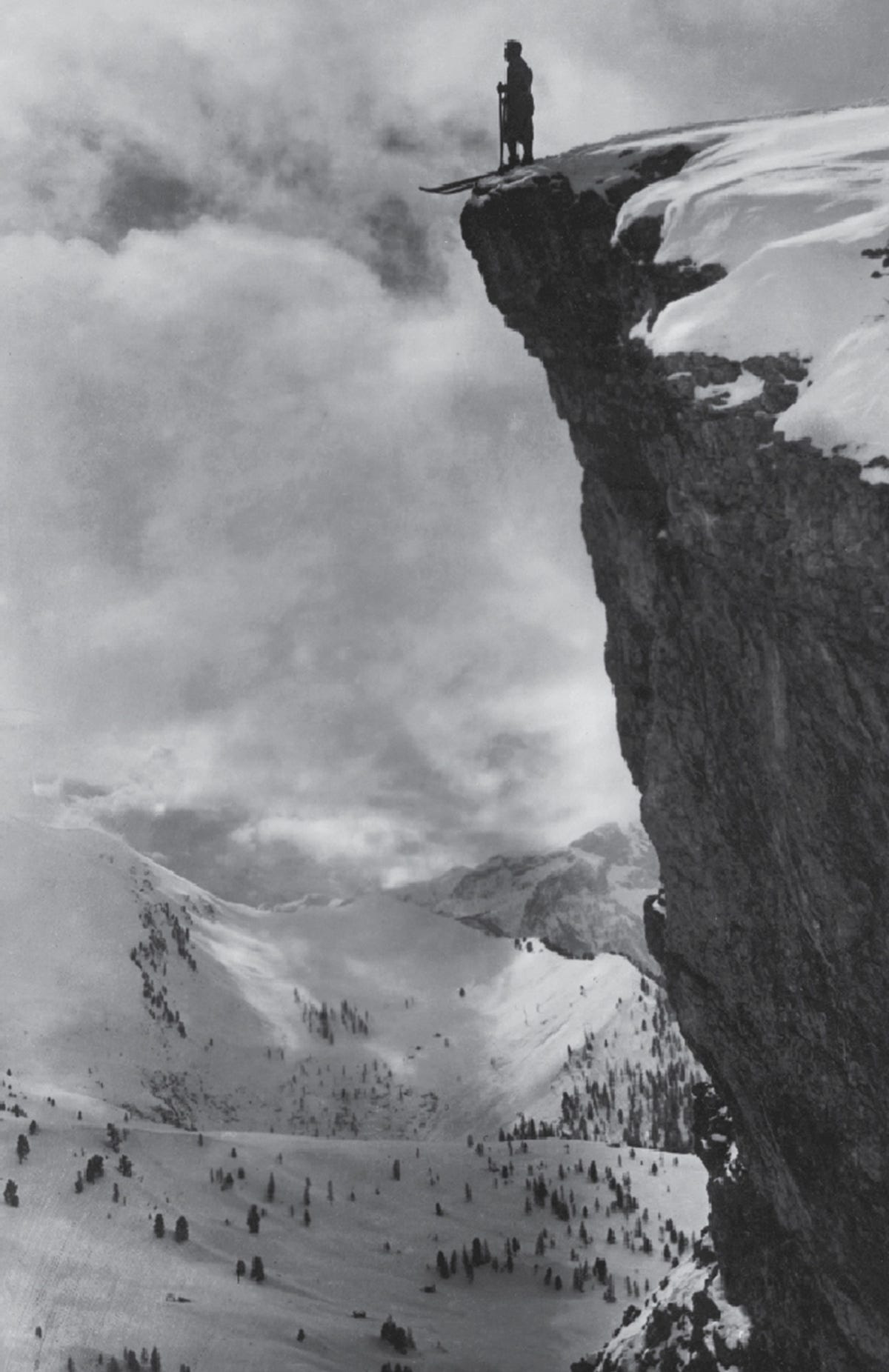

The bergfilm is a characteristically German endeavour which enjoyed immense popularity in the Weimar Republic; these films were set high in the mountains, transcending cosmopolitan grime in order to present present man’s desires, passions and struggles on a purer ethereal plane. The white peaks of the mountains, where Death always lingered, tested the vitality and spirit of those who were compelled to ascend and conquer it, this human drama occurring over the sublime backdrop of German nature. The bergfilm had an undoubted contribution to the recovery of the German identity in the years following the Great War; though not overtly political, it provided a clear and cohesive aesthetic that unified the fragmented and demoralised German perception of themselves. Perhaps this is why most bergfilm did not need a particularly sophisticated narrative in order to be appreciated by the public; much of the thematic heavy lifting was done by the meta-narrative. Perhaps this is also why the bergfilm waned in popularity during the war-time and post-war periods, which had little patience for its themes.

I. The Holy Mountain

The Holy Mountain, which Leni would star in, was director Arnold Fanck’s fifth bergfilm. All of Fanck’s films followed his particular vision, which was to present Nature in her most beautiful and unadulterated form to the audience so that they may experience it as authentically as possible. Fanck did not shoot his films in the comfort of studios, but insisted that they be filmed on the mountains, where he subjected himself, his staff and his actors to dangerous weather, treacherous slopes and unpredictable conditions. Fanck was an expert skier and mountaineer and expected the same of his team if they were to keep up with his highly physical style of filming. The actors, actresses and film crew had to carry heavy cameras, studio equipment and countless reels of film high up into the mountains, where they often spent months filming under adverse conditions. The risks taken should not be understated; Leni broke both of her ankles on the first day of filming, but persevered as she was driven by a pressure to keep up with her experienced male co-stars. There was an undeniable pride taken in this style of filming, for the physical ardour purified the intentions of the cast and crew as they set to work realising Fanck’s vision of using raw natural elements to create visual art.

For Fanck, it was the mountain that was the star of the film; priority was given to conveying its reality authentically over intricacies of plot or appeasement by spectacle. This, however, did entail a casualty of storytelling in Fanck’s films, where the plots were rightly criticised as being overly simplistic. The Holy Mountain presents a generic love triangle between the dancer Diotima, played by Leni, and the man she loves, Karl. Karl’s best friend Vigo secretly loves Diotima. Both Karl and Vigo are mountaineers, but for Karl the mountain serves a particularly intimate purpose; it is place of revelation where he goes to understand his inner-self. When Karl first sees Diotima, he retreats to the mountain to process the turbulent emotions raging within him, but Diotima and Karl eventually fall in love and are engaged. In a misunderstanding, Karl mistakes a platonic gesture between Diotima and an unknown other man and retreats to the mountain in a jealous fury to process his emotions. He takes his friend Vigo along with him, but on the rockface during a dangerous storm, Karl finds out that Vigo was the other man. In the heat of the ensuing confrontation, Vigo falls over the edge, still tethered to Karl. Forgetting their differences, Karl holds tightly to Vigo’s rope and awaits rescue. Amidst the raging storm, he eventually realises that he cannot pull his friend back up, but refuses to let him perish, despite Vigo’s insistence that he cut the rope. Exhausted from holding him up, his thoughts with Diotima, he allows himself and his friend to fall together. After the storm, hearing of what happened, Diotima mourns the love and loyalty of the two men lost to the mountain.

The Holy Mountain cemented Fanck’s reputation as a masterful and technically brilliant director and paved the way for future films. With Leni starring, he went on to direct The White Hell of Pitz Palu (1929), Storm over Mont Blanc (1930), The White Ecstasy (1931) and S.O.S. Eisberg (1933). Leni would brave further physical challenges, sometimes bordering on sadism, in order to maintain authenticity in all of her performances. Her hard work did not go unnoticed by her audience and she was catapulted into stardom as a result. She made her directorial debut in The Blue Light (1932), which was praised for its pictorial beauty and Leni’s innovations in her role as an editor and director. This film caught the attention of a certain Adolf Hitler, and the rise of National Socialism would have an impact on the career and lives of both Leni and Fanck.

II: Symbolism in the Bergfilm

The genre of bergfilm reached its heights well after the Golden and Silver Age of Alpinism, of 1854-1865 and 1865-1882 respectively, where countless summits were conquered in a remarkably short time as a matter of exploration, ambition and scientific discovery. This was a far cry from modern mountaineering, a recreational activity that though carrying some risk, is considered generally safe and accessible to the public thanks to modern technical equipment, experienced guides and well-mapped routes. But between the Age of Exploration and the Age of Recreation, stands the Age of the Bergfilm, where the mountain was climbed for the sake of artistry; the bergfilm was an aesthetic extension of mountaineering itself and explored the symbolic and spiritual value of the mountain independent of exploration or recreation.

Symbolically, the mountain is immoveable, stable and monolithic; its topography is resistant to perceptible change even across multiple human lifespans. It is indifferent to the aspirations of those who look upon it, those who climb it and those who perish upon it. From Mahameru to Olympus, Fuji, Sinai, Tlaloc and Hara Berezait, the high peaks are the divine residence of deities and central to many myths of cosmogony, thus making every ascent a mortal trespass into a mystical realm. Symbolically, the ascent represents a gruelling purification of the mind, body and spirit, with the peaks and slopes representing a natural sanctuary untainted by worldly corruption. It is here that one encounters revelation and self-knowledge. To be sure, the mountain itself can never be conquered, but only ascended upon for a brief time before the homeostatic fragility of the climber can no longer withstand the harsh clime. The aesthetic of Faustian defiance to this reality is infused into the visual language of the bergfilm; its men and women are strong, wilful, moral and independent, their turbulent passions are innocent and naively childlike. They drive themselves to the summit on account of these passions, whether it be love, arrogance, ambition or pride, with the ensuing tragedy serving both as a cautionary tale and a testament to the intractable human spirit. Death on the mountain is seldom meaningless; in The Holy Mountain, Karl’s death represents loyalty and in The White Hell of Pitz Palu, Krafft’s death to save the young Hans is the ultimate sacrifice. Thus to die in the pursuit of the summit is a noble and heroic death which rejects the mundanity of existence beneath the peaks; the body and spirit of the climber undergoes metaphorical petrification as it is incorporated into the body of mountain lore.

Through the bergfilm, the German spirit and identity are implicitly re-crystallised through association with the mystically sublime landscapes of the fatherland. The vigorous rise and ignominious decline of then-recent German fortunes is valorised in the wilful determination of the ascent and the fatal risk of disaster that comes with such defiant ambition. It is unlikely that this symbolism was purposely aligned to reflect the political mood of the era, but it cannot be denied that it achieved this alignment remarkably well. The aesthetics of National Socialism may have found inadvertent expression in the bergfilm, but at least early on this appears to be a coincidental overlap of themes that were resonant with the public at the time. The recurring appearance of former World War 1 ace pilot Ernst Udet in Fanck’s films could cast some doubt here, but it is not compelling evidence in of itself. Indeed, through the test of time the symbolism of the bergfilm finds itself absolved of political affiliation; today Fanck’s films are seldom ideologically edified in comparison to the works of Riefenstahl and D.W Griffith. The modern view of the bergfilm is more likely to lean towards spiritual or humanistic interpretations before propaganda.

III: Legacy

The fate and fortunes of Leni and Fanck would diverge after their last film together, S.O.S. Eisberg (1933) which was based on a doomed polar expedition. Leni’s performance as director and star of The Blue Light had caught Adolf Hitler’s attention, who asked her to direct a film about the fifth Nuremberg rally. Following the success of The Victory of Faith (1933), Leni went on to direct the iconic Triumph of the Will (1935) which cemented her reputation as Germany’s foremost director. Hitler invited Leni to film the 1936 Summer Olympics; Olympia (1936) is considered an aesthetic and technical masterpiece, with prolific use of tracking shots, slow motion and aerial shots to create striking visuals that gained her worldwide recognition. Immediately after the war, Leni was detained and put on trial to account for her cooperation with Hitler, however nothing incriminating was conclusively proven beyond a circumstantial sympathy for National Socialism. Leni was never truly absolved of her association and spent much of her life defending herself against her accusers. Despite this, she went on to have a celebrated career as a photographer, documentary film-maker and environmental activist. Leni passed away in 2003, a day after her 101st birthday. Leni’s legacy demonstrates an unmistakeable creative talent in the visual arts, her remarkable aesthetic sense is matched only by her psychological intuition in depicting the vitality and physicality of the masculine spirit as she understood it.

Unlike Leni, in the 1930’s Fanck found himself at odds with the ruling party due to his reluctance to cooperate with Goebbels, a decision that hastened his decline in visibility and popularity. He eventually reconsidered his position and agreed to direct propaganda films, with The Daughter of the Samurai (1937) being the a notable co-production between Germany and Imperial Japan. However his career would never return to the heights experienced during the peak popularity of the bergfilm. His reluctant cooperation with National Socialism did him no favours after the war; his films were banned by the Allies rendering him a persona non grata who no longer received any offers for work. With little recognition and in financial difficulty, Fanck spent his final years much as he spent his early life; he retreated to the mountains, working as a lumberjack until his death in 1974. Today, Fanck is remembered as a brilliant technical innovator, a daring film maker and the undisputed father of the bergfilm.