Wagner's Parsifal and the Problem of Identity

Reconciling tensions between the masculine and feminine spirit.

Wagner’s “sacred festival play” Parisfal recounts a knight’s search for the Holy Grail, an old story of spiritual endeavour that is made relatable to the modern psyche. The setting may be that of Christian chivalry amidst sorcerers and castles, but Wagner’s psychologically complex interpretation explores wholly modern problems. The problem of identity is central to Parsifal’s struggles and remains relatable to its audience who must contend with their own identity’s allegiance to opposing forces of culture, nationality, race, spirituality, art and entertainment. Wagner hopes to provide a solution to this crisis of identity through Parsifal. However, these problems and solutions do not need to exist on the grand scale of humanity as a whole and can instead be explored on an intimate level. Identity and spirituality is as much a personal problem as a collective socio-political one, if not more so. Viewed as such, Wagner explores psychology of the Self without resorting to tiresome psychoanalytic jargon siphoning the vitality from the insights obtained.

The story of Parisfal is of convergence; its protagonist is initially formless in identity and ambiguous in provenance, but we see him take shape through trials and lessons. It is not just the idea of a dissimulated identity that converges here, but also of the opposition of the male and female that is characteristic of the modern sexual crises and its dynamics. The “holy fool” Parsifal’s masculinity and the “vile sorceress” Kundry’s femininity, are both dealt with compassion which ultimately resolves their tension. Thus the problem of identity is not only tackled on a personal level, but also on an interpersonal one. At least this is what Wagner hopes, as his intention points towards a story that is unifying, spiritually insightful and engenders compassion in its audience. The ability of the work to delicately challenge and modify pre-existing thought helps give it lasting appeal and Wagner’s play does indeed endure in comparison to the transient popularity of works that simply entertain and confirm convictions rather than explore them.

George Bernard Shaw wrote (of the Ring Cycle) that if the aptitude of the audience was lacking, Wagner’s work would be reduced to a series of petty squabbles and hours of scolding and cheating by fairytale personages. “Only those of wider consciousness can follow it breathlessly, seeing in it the whole tragedy of human history and the whole horror of the dilemmas from which the world is shrinking today.”. Shaw’s biases as a Wagnerite and his overly political interpretations are clear, and he too is inclined to stage his conclusions on a grand scale rather than a personal one. But his sentiment remains accurate, as Parsifal allows the inner self an opportunity to explore and contend with the “horror of the dilemmas” that it is increasingly numb to.

I. Identity and Origin

The loss of identity is what Parsifal and Kundry struggle with and it is tied to the stories of their origin, thus forming the key thematic link between them that allows them to deeply understand each other, more so than they are understood by anyone else. This bridge is the means by which compassion is given and received, which ultimately concludes their respective character arcs.

Parsifal’s ignorance of his past leads him to have no firm convictions about his present; his childhood memories are disconnected fragments at the precipice of his recollection, so he must rely on others, such as Kundry, to reveal the elusive details that he cannot unravel himself. Name and origin are integral to the formation of an identity for it is to that which experiences and attributes are first attached. A nameless identity inevitably becomes fragmented and entirely referential to others, which leads to a state of existential listlessness, the very state we first encounter Parsifal in. He enters manhood feeling othered and aimless, wandering through the forest acting on primitive instinct without any semblance of a higher consciousness.

In contrast, Kundry’s identity is well formed from the outset but presents a complex series of contradictions. Like Parsifal, she struggles with her past and its effects on her current identity, but unlike Parsifal, she has self-knowledge, which is what he intrinsically seeks. Parsifal is a pure innocent, whereas Kundry is tormented by her past and defined by the worst aspects of herself. Parsifal has the ability to feel compassion, whereas Kundry earns only the revulsion of others. Parsifal is free to roam the wilderness whereas Kundry is trapped in an endless cycle of penitence and seduction, which is all her identity is reduced to. The cyclic nature of Kundry’s suffering has a supernatural exoticism to it, through the extra ecclesiam implication of rebirth and reincarnation. Parsifal is presented to the audience in a state of pure simplicity, whereas the “sorceress” is full of contradictions for she is both a messenger of the Grail and also allied with the manipulative fallen knight Klingsor. Klingsor gleefully reminds her of her past and the many names she went by when she carried out evil deeds; First Sorceress (Urteufelin), Hell's Rose (Höllenrose), Herodias, Gundryggia and finally, Kundry. Like Parsifal, she has many nicknames and these weaken her identity and obscure her original self. Through this complex backstory her role as Parsifal’s thematic foil and counterpart is made apparent to the audience.

II. The Problem of Identity and its relation to Parsifal

Modern man, as Wagner observes him, shares in Parsifal’s loss of identity; he is indoctrinated with a strong sense of individualism through his humanistic education but his environment seeks to define and redefine that individual identity according to what is politically and economically expedient. He must voluntarily and individually partake in a collective of his choosing, but his choices are preemptively limited by contemporary relativistic societal values. The non-relativistic options are either censored or only made available in extreme polarised interpretations, which limits dissent to reactionary and radical pipelines. His spiritual intuition is muted by the assault of both atheism and excessive religious formalism, which at best confuses and at worst misleads entirely. He is able to relate to Parsifal’s crisis of identity, for his own identity is diffuse, fluid and uncertain unless he adopt ready-made, spiritually barren and ideologically homogenous commodity-identities available to him. Opportunists will take advantage of this vulnerability and offer ideological alternatives that serve political, economic or material ends that are often against the interests of the psychospiritual self. This disenfranchised mind, similarly to Parsifal, desperately seeks to recover its identity. Whereas Parsifal seeks to uncover a forgotten past, the modern counterpart tries to recover what has been obscured by relentless relativising of normative values and a spiritual “drying up” characterised by a lack of direction or compassion. But this recovery must begin with the acceptance of non-identity and an acquiescence to spiritual intuition guided by compassion. In other words, he must embrace the humbling reality of being naive and innocent of all knowledge relating to the self, much like Parsifal’s natural state when we first encounter him. It is from here that they may begin their quest for the Grail; that is, the path to a higher spiritual Truth.

In Parsifal, our protagonist presents a near-perfect picture of ambiguous identity. His ignorance of his own name, his past, his culture and his kin means that he “starts from zero” with respect to his self knowledge. His innocence is like that of a child, but lacking the anchoring quality of the “self” from which they can inquire and explore the world. Parsifal’s unencumbered inquiry is far freer in some ways and far more limited in others. It is free in the sense that there is no lens of the ego colouring the experience, allowing him to curiously explore human complexities with a simplicity of intent. It is limited as without the anchor of identity and proper guidance there is a danger of endless, listless wandering without purpose, which is where we find him in the first act. When wise old Gurnemanz sizes him up on their first meeting, he fears that this is all that foolish Parsifal is destined for.

In the opening act Gurnemanz witnesses Parsifal wander aimlessly into the sacred precinct where the Grail knights are stationed and shoot down a passing swan with his hunter’s bow. This is the instinctive act of a child with no knowledge of pain, death or consequence, done for its own sake and with no real motive other than curiosity. The very image of simple Parsifal armed with a bow and arrow has an element of inevitability to it, much like how humans are inevitably compelled to exercise their ability to cause emotional, physical and spiritual pain to each other. When wise Gurnemanz draws the lifeless beauty of the swan to Parsifal’s attention, Parsifal is stricken with grief and breaks his bow. This is a symbolic act, not of pacifism (for we see Parsifal develop into a knight) but of an innocent identifying a profane extremity for the first time and establishing a boundary for himself beside it. This is the first instance of Parsifal forming a sense of self in the differentiation between what is good and what is evil. Previously wandering, his moral compass receives a calibration to inform his future journey. This idea of the innocent inquiry of a fool and normative recalibration through the principle of compassion is central to Wagner’s solution for the spiritual decline of modern man.

In Parisfal, the “foolish” primitive state is presented as an ideal and fertile ground for genuine spiritual experience, learning and wisdom. It is a blank slate (mushin) that allows for clear internal and external perceptions unburdened of history and indoctrination. Wagner idealises the simple and universally accessible act of compassion as taking spiritual precedence over self-important pomp and pageantry. Parsifal has no name, identity, title, status, heritage, ancestry, identity or culture. Many traditions identify attachment to an identity rooted in the material world to be an obstacle to spiritual realisation, which is why they emphasise the exoteric practice to establish a receptive state before fully engaging in esoteric de-attachment. However, an aimless annihilation of identity only leads to existential wandering without purpose, which is the initial state we find Parsifal in. Detachment from material constraints must coincide with prior attachment to a higher principle, otherwise there is no benefit from it. Upon breaking his bow, Parsifal departs from his ignorant state and attaches himself to compassion as his guiding principle. He then channels and directs the expression of this principle through striving for the grail, adopting an exoteric religious framework to further refine his inner conviction.

Wagner reminds modern man, deeply entrenched in a crisis of identity, that he is closer to this ideal foolish primitive state than he thinks. If he is able to recognise his manufactured artificial identity as illusory, he discovers that he too is “starting from zero”. When the illusion of his modern identity crumbles, the carefully constructed hypocrisies upholding this identity may also crumble and leave bare earth on which to lay new spiritual foundations. This foundation must categorically be governed by a higher principle, lest one false identity be exchanged for an equally empty identity in religious garb. For Parisfal, Wagner chooses compassion as this ideal principle. Thus we see him, unencumbered by material, emotional or historic baggage, devote his active energy to compassion rather than ambition. In his active devotional state we find him receptive to spiritual realisation, with Enlightenment transposed from the Buddhist conception to the medieval Christian symbols of the Spear and the Grail. Emphasis on the seed of a higher principle taking root is fundamental in avoiding a narrow literal reading of Parsifal as merely a religious play. The imagery and symbolism is undoubtedly Christian but Wagner provides subtext inspired by eastern thought that gives a perennial applicability of the message.

Finally, Parsifal’s character, insofar as it is presented or interpreted as a solution to modernity, ought to be considered practically as well as esoterically. Modern man would find it a difficult task to acquire innocence and compassion as easily as it was granted to Parsifal. As part of his own quest, he must recognise that innocence and compassion are interior qualities and ideals that must be strived for through outer action, in the hope that they take seed within. In turn this outer action must be supported by the initiatory structure of faith including meticulous adherence to prescribed doctrine. This inner seed will then grow into an holistic expression of innocence, compassion, detachment and the chaste virility that is presented in Wagner’s Buddhist influenced ideal. This spiritual ascension is nothing less than heroic, as conceptualised by Wagner with his own predisposition towards sentimentality. In truth, a spiritual journey has no generalisable form or structure, but we rely on Wagner to provide a beautiful and comprehendible example that is widely accessible.

III. Kundry

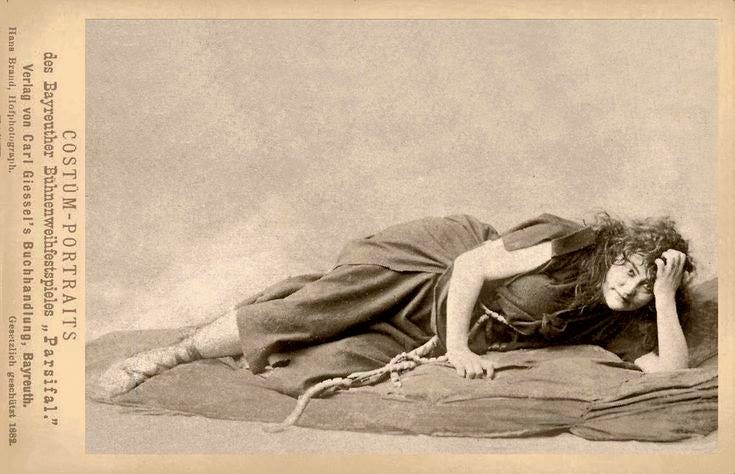

If Parsifal is the potential of an undefined past and an unencumbered self, then Kundry represents the limits of a demoralised self whose identity is fragmented and irredeemable. She expresses a profound disillusionment with the weakness of man and the ease with which he falls to her temptations. Her characteristic sensuality represents the burden of femininity that the modern woman must navigate through, but her disillusionment speaks to all. Kundry’s character is less idealised than Parsifal and for this reason is more relatable, pitiable and emotive to the audience. She is altogether more human, with her inconsistencies and contradictions existing alongside her cautious hope of redemption.

We discover that Kundry’s suffering began when she witnessed the Redeemer, Wagner’s ideal of spiritual perfection, but unforgivably mocked and rejected him as he suffered on the cross. Schadenfreude is said to be the least compassionate of all human emotions and so Kundry is fated to suffer the bitterest punishment. She is destined to relive her shame in an endless cycle of rebirth where “the salvation of eternal sleep” eludes her until she can encounter someone of similar spiritual perfection who will resist her wickedness and provide her with redemption. Thus she lives many lives, is called by many names, wanders endlessly and is not permitted to weep, only to jeer and mock. The centuries go by and Kundry forgets who she is, remembering only the wrongs that she has committed as if in a never ending fever dream. Her identity is a negation devoid of any positive quality as she becomes defined by her transgressions. Wagner acknowledges that Kundry made a catastrophic mistake in her rejection of Christ, but subtly reminds his audience that it was a very human mistake that they would be unwise to judge too harshly. Who can confidently say that they could recognise divinity if it were to proclaim to walk amongst them? Kundry, despite her garish sexuality, manipulations and pathetic helplessness, is not deserving of contempt, but the audience’s compassion. Without compassion towards someone as reprehensible as Kundry, what hope can the audience hold for their own salvation?

Kundry is written to parallel the plight of the modern woman, who finds her identity increasingly sexualised, commodified and spiritually weakened. Much like her male counterpart, there is a general movement to celebrate and accentuate the natural weaknesses of her sex to create an uncertain, pliable and frivolous class of consumer. Her femininity is no longer tied to her spirituality, but to physicality either as an object of sexual gratification or of utilitarian motherhood. She finds her counterpart, man, devoid of any spiritual virility and unwilling to recognise their complementary natures unified by a higher principle. Thus, rather than cooperative roles based on the specialised qualities of either sex, there are extremes of total subjugation or complete independence from he who should be her ally. Woman’s disillusionment runs deep when their subtle introspective remembrance is numbed by the crudeness of distraction, consumerism and entertainment.

Kundry too suffers from profound disillusionment. She fundamentally seeks redemption through the compassion of a man who can look past her seductive exterior femininity to validate and embrace her with love that fulfils her soul. She is trapped by her curse and has no choice but to seduce and mislead men, not being permitted to engage them in any other way. Although she hopes to find redemption amidst these compelled seductions, she only witnesses multiple cycles of well intentioned, upright but ultimately worldly men falling short of their professed ideal. Her corrupt environment compels her to remain corrupt as she is obliged to corrupt others. She yearns for compassion whilst holding the weakness of man in contempt. The weakness of man cannot see her beyond her carnal identity of womanhood and can therefore provide her with no absolution from her sins. Though she holds these weak men in contempt, they too hold her in contempt as she is the corruptor of the well intentioned and sullies those who seek to attain purity. She finds no protector amongst them and thus she is vulnerable to exploitation and ill treatment. When we consider the Christian principles of forgiveness and charity in this play about the quest for the Grail, we find that Kundry is most in need of it and yet is most often refused it.

Mirroring Kundry’s identity of negation and disillusionment, modern men and women are encouraged to hold each other in a state of psychospiritual contempt but physical co-dependence. It would be presumptuous to say that women look for “redemption” in men. It is less controversial to say that both men and women fundamentally seek companionship and comfort in each other as they seek something higher than themselves. Disruption and denial of this bond leads to feelings of underlying hostility, contempt and self-assured feelings of independence from the other. Independence from the idea of being reliant on the other morally frees them to mutually exploit one another for physical satisfaction. Sexual relations go from rewarding and unifying pleasure, to a soulless Foucaultian power play. At such extremes, is it any wonder than many can relate to Kundry’s disillusionment when it is placed before them?

III. Parsifal’s Trials and Kundry’s Dilemma

Parisfal’s quest comprises of trials that symbolically represent a transition from a lesser outer struggle to a greater inner struggle. When he approaches Klingsor’s castle he pits his strength against that of the defending knights, defeating them with ease. But his entry into the enchanted garden marks the transition into a subtle plane where his inner qualities are put to the test. These trials are a common motifs in many chivalric stories; a knight must face trials of strength and character in order to prove his worth, some being so contrived that they prompted a thorough lampooning by Cervantes. But these trials ought to be considered esoterically as a means to ensure the fulfilment of mystical prerequisites on part of the aspirant.

So, in this enchanted garden, Parsifal encounters the seductions and temptations of the flower maidens, who compete with each other for his attention. The danger of such distractions has already been illustrated in the example of Amfortas who, despite his knightly strength, perished to Kundry’s temptation and lost ownership of the Holy Spear. The trial of the flower maidens has familiar counterparts in the Western narrative tradition, but Wagner looks towards the Rig Veda to find an equivalent in the daughters of Mara the Asura. Hindu and Buddhist texts recognise these daughters as Rati (representing lust), Arati (discontentment) and Tarasna (craving, longing and desire). These three daughters attempt to distract the Buddha Shakyamuni from his ascetic path to Enlightenment just before he reaches it, as reported in the legendary biographies of the Maharasta, Nidankatha and Lalitavastra. Like Shakyamuni, Parsifal is on a path to Enlightenment and must navigate through these distractions, but unlike Shakyamuni, Parsifal is not a holy man but an inexperienced holy fool on the outset of his journey. Fortunately for Parsifal, his innocence (the idea which Wagner asks us to aspire to) renders him immune to the temptations of the flesh. Frustrated, the maidens abandon their efforts and bicker amongst themselves. Parsifal’s ease at overcoming this trial is intended to be instructive; pleasures of the flesh are easy to identify and overcome but temptation takes forms that are infinitely more subtle that the aspirant must guard against. It is these subtler forms that Parsifal must contend with when he encounters Kundry, who is under Klingsor’s manipulations when she is sent to defeat him.

Kundry’s approach to Parsifal is informed by her keen intuition and witnessing the failure of Klingsor’s lackeys to either overpower or seduce Parsifal. Instead, Kundry tempts Parsifal with what he is aware he lacks; self-knowledge. She puts on a compassionate guise and leverages the pure and sacred love between a mother and child to achieve her ends. She calls Parsifal by his name, a clue to his identity that he has long forgotten and that could only be known to his beloved mother, now a fading distant memory. Kundry recounts to him the story behind his name and tempts him with the answer to one of his most fundamental questions. “Who am I? Why and how did I get here?”. Kundry provides Parsifal with self-knowledge, but in narrow, linear and material terms which are ultimately a misdirection. Though knowledge of genealogy and ancestry has its place, it only offers a point of reference for others and cannot provide us with a whole identity. Wagner reminds us we cannot be told who we are by others, but must look to our own experiences in pursuit of a higher consciousness. Kundry’s attempt to inverse this truth provides Parsifal with an answer that is materially satisfying but metaphysically empty.

Kundry doesn’t offer Parsifal knowledge to bring him a sense of peace. She mixes it with manipulative half truths to create an upheaval in Parsifal and render him vulnerable to emotion and sentimentality. She implies that Parsifal shares guilt in his mother’s passing and causes the fires of self-reproach to spread within him. She poisons Parsifal with her words and in the same breath offers him an antidote. She kisses Parsifal with the pretext of transferring maternal comfort, but Parsifal’s intuition recognises her false solution to a false problem. The kiss elicits a psychosomatic memory of Amfortas’s painful wound, a reminder of his downfall, and Parsifal cries out in pain and retreats from her advances. This is his final trial and once overcome, he is able to defeat Klingsor and gain rightful possession of the Holy Spear.

Kundry’s corrupt actions are not the unthinking plot devices of a generic femme fatale, the type that are sensuously presented and soon dismissed after achieving their narrative purpose. Kundry suffers because she is aware that she is fundamentally out of synchronicity with a higher moral order. She considers herself incompatible with the “good” and yet feels a magnetic pull towards what she hopes is “pure” so that she may herself be cleansed by it. One can see that Kundry is drawn to Parsifal by the hope of his incorruptibility as much as the intention to corrupt him. So as Kundry corrupts, she unconsciously seeks that which is beyond her corruption and therein lies her hope for redemption. Kundry suffers because her experiences have chipped away at this hope to the point where she doubts whether she will ever be redeemed. Kundry exists in a state of deep self-loathing, which is another parallel that can be drawn with the modern identity. This identity struggles to be sure of anything beyond its own impermanence and irredeemability and thus it finds satisfaction in seeing this ugliness extended and reflected in the world around itself. Corruption is not content to exist alone, but would rather exist as a corrupt part of a corrupt whole. The mystical point of view would emphasis the balance and symmetry that exists in all things by design, thus the corrupt whole ultimately wishes to be part of a magnificent, incorruptible and pure Absolute, much like how Kundry deeply desires redemption.

IV. Good Friday

Parsifal obtains the Holy Spear at the end of Act II, however obtaining this holy relic this does not herald the end of his quest. It is not enough to obtain this mystical power, but his trial is now to take it with him into the world. When Gurnemanz and Kundry encounter him in Act III, he emerges wearily, clad in armour, from the obscuring density of the forest. He carries the spear and informs Gurnemanz that he suffered many wounds in preserving the sanctity of this relic, that is, by not wielding it in battle. Parsifal recognises, and is recognised by, Gurnemanz and Kundry. Kundry herself awoke shortly before his arrival, as if in anticipation, and has already been anointed by Gurnemanz with water from the Holy Spring signifying her ritual purity on this holy day.

The convergence of these three characters in the Holy Precinct on the holy day of Good Friday is no coincidence, but an act of Providence. Gurnemanz recognises the auspicious timing and instructs Kundry on purifying Parsifal from “the dust of long wandering”. They remove his armour, signifying the conclusion of the trial and that Parsifal nears the end of his quest. Touchingly, Kundry washes Parsifal’s feet with the holy water and dries them with her long hair whilst Gurnemanz anoints his head. In the emotional climax of the play, now ritually purified, Parsifal takes a handful of the holy water and baptises Kundry in the name of the Redeemer. He compassionately kisses Kundry on her forehead, signifying the end of her centuries of torment.

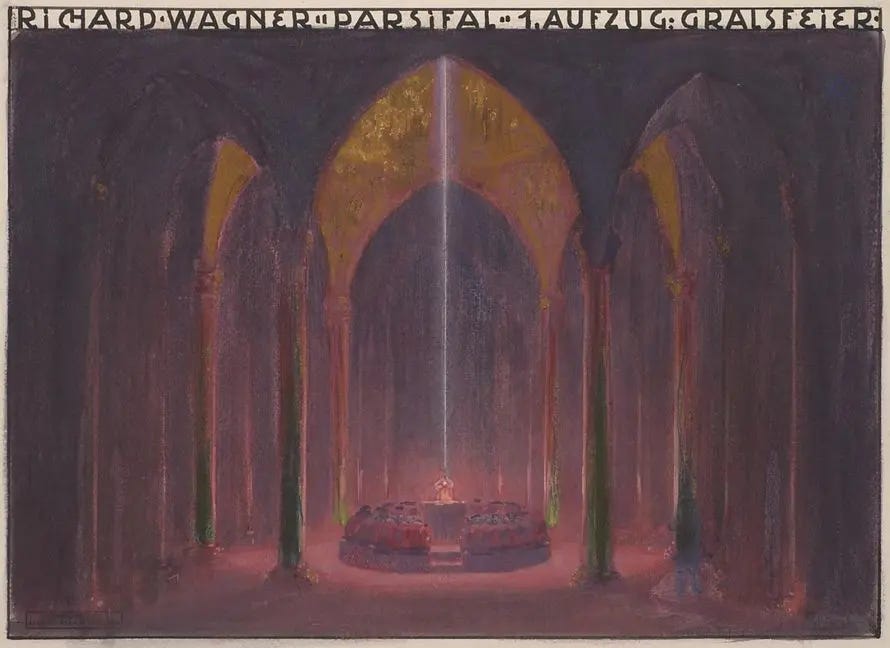

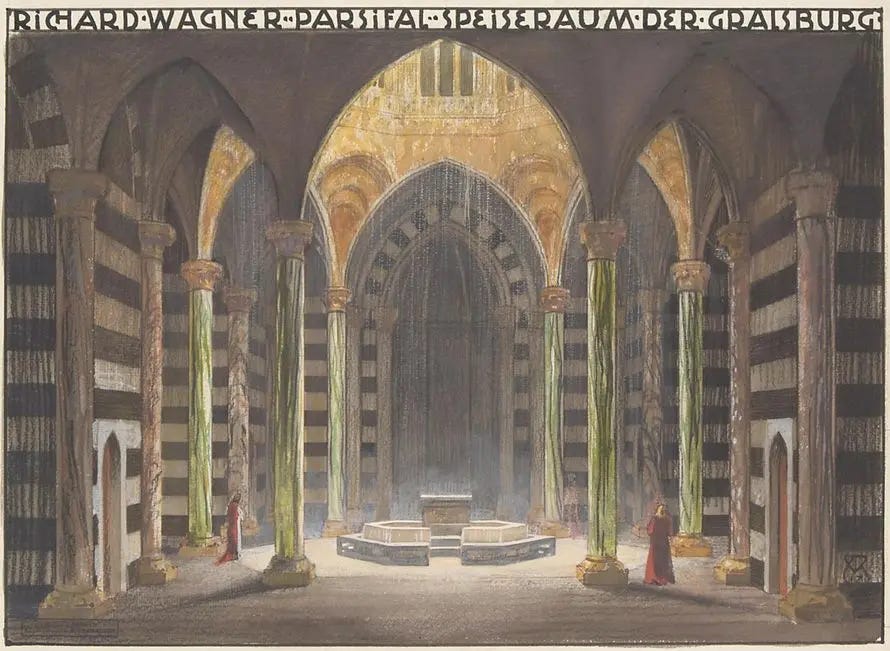

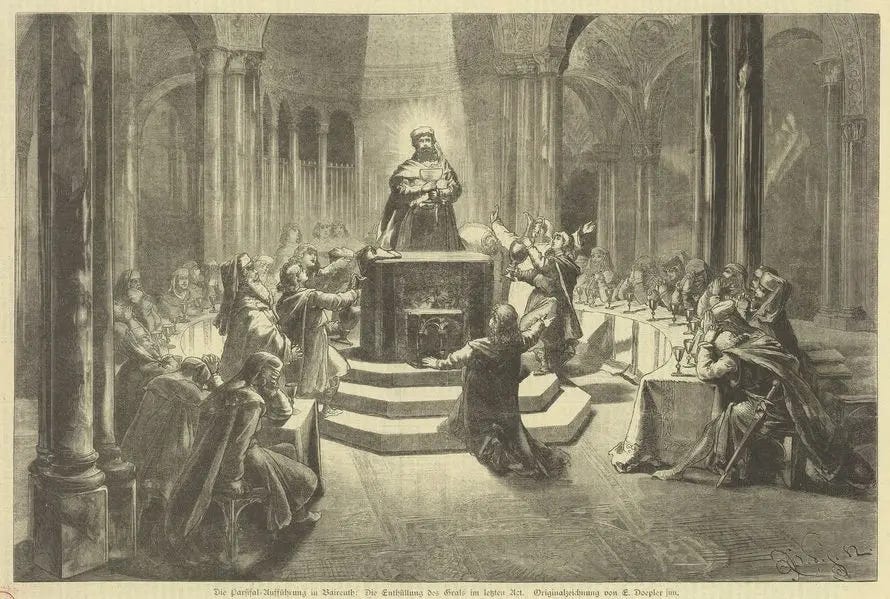

In this scene, the tension between the male and female identity is resolved. Kundry purifies Parsifal and Parsifal absolves Kundry through the higher principle of compassion. It also highlights their complementary roles in the pursuit of the Grail, Without Kundry’s suffering there could be no manifestation of Parsifal’s compassion. With Kundry’s redemption, the audience must consider the possibility of their own redemption and the means by which it could be achieved. The final scene of the play, where Parsifal holds the illuminated Grail over those assembled in the great hall, the audience experiences edification under the divine light of compassion and redemption.

The powerful themes and symbolism of the final act of Parsifal rattles the sensibilities of the modern viewer. Through overt religious imagery and mystical undertones, it demands response and rebuttal from the religious and irreligious alike. Those who practice faith without internally adhering to higher principles such as compassion are encouraged to recalibrate their moral compass. Those who tie their identity to modernity and experience a consequent spiritual sickness are offered a momentary, crude but on the whole effective aesthetic experience that spans faith and redemption. Perhaps Wagner wished his audience to walk away from the play believing in something, rather than nothing.

V. Conclusion

As we have seen, Wagner’s work is a modern expression for the desire for ritual and tradition infused with religious meaning. We see its impact in the cult that formed around him during his life and in the continuation of the annual quasi-religious gathering at Bayreuth in the years since his death. Parsifal and Kundry are themselves a synthesis of pre-modern mythical archetypes that seek to navigate the concerns of a modern audience whilst striking a resonant chord with their dull and distracted passions. But to edify Wagner as a prophet and Parsifal as a prophecy is to succumb to the illusion of self-knowledge represented by Kundry’s kiss. Instead we recognise that Wagner’s themes and symbolism alludes to a greater spiritual tradition that his modern audience is encouraged to engage with and benefit from.

“Only those of wider consciousness can follow it breathlessly, seeing in it the whole tragedy of human history and the whole horror of the dilemmas from which the world is shrinking today.”

On this basis we may take issue with Shaw’s remark. Parsifal requires no elitist pre-requisite of a “wider consciousness” to understand its spiritual message, the centre of the work can be accessed directly and simply by all. A well read member of the audience will appreciate the depth and complexity of the message, but its applicability extends to all current affected by the modern condition. Wagner’s characters struggle with their identity, so that his audience can apply lessons learned their modern problems. Thus it is accessible to all who suffer, provided that they are made aware of their own suffering. As Wagner says, “if (this) suffering can have a purpose, it is simply to awaken a sense of fellow-suffering in man”.

Parsifal can be appreciated in many ways, with some likening its performance at Bayreuth to a religious experience. Some may find themselves touched by the music, others by the theatrics and others still by the poetry of the libretto. Though Wagner’s genius has its part to play in the mesmerising qualities of Parsifal, one can’t help but see the infusion of luminescent residues of transcendent themes that he took his inspiration from. The luminescence of these residues in turn gives light to those that find themselves confused and disillusioned by the darkness of modernity.