Charismatic Leaders and Charismatic Communities

A Theory of Personality, Influence and Devotion

“To the god-like Individual of our times; the Man against Time; the greatest European of all times; both Sun and Lightning: ADOLF HITLER, as a tribute of unfailing love and loyalty, for ever and ever.”

-Savitri Devi, The Lighting and the Sun

So begins, with the above dedication, Devi’s The Lightning and the Sun; with awe she writes of he whom she ascribes semi-divinity, an Avatar of Vishnu, a man against time, a man who she believes is of irreproachable moral energy untouched by the Dark Age and the one who struggles for the “reign of righteousness” as intimated in the Bhagavad Gita. Devi’s intense devotion to her Führer is palpable through the pages of her work, as is her desire for the reader to be edified, as she was, by his example. She attributes superhuman qualities to Adolf Hitler, saying that he embodies the qualities of both the Lighting1, the great devastating force of Nature, and the Sun2, the creative and unifying defiance against the downward trajectory of the Dark Age. With hagiographic adulation, she describes the subtle, noble personal qualities of her ideal emerging from infancy and finally manifesting in manhood. For Devi, the moral character, triumphs and even defeat of Adolf Hitler lined up with the perfect rhythms of a Cosmic order and the destiny of man, against time, to reach the perfection of a Golden Age3.

Devi’s appraisal of her charismatic leader, in relation to Carlyle’s On Heroes, Hero Worship & the Heroic in History, views him not as a Hero as King, nor as a Hero as Prophet, but a Hero as Divinity4. Many today would regard Devi’s deification of Adolf Hitler as an impassioned overreach in zealotry and in extremely poor taste. Some may even consider her, in her foreign garb, with countless eccentricities and questionable allegiances, a laughably bizarre character altogether. Before she is mockingly dismissed, it is worth considering that, rightly or wrongly, she was moved by a conviction of an inviolable truth, and however irrational we may find the conclusions, we form part of a collective that is moved in the same way to the seemingly irrational, whether we know it or not.

The study of charismatic leaders, of course, predates both Carlyle and Devi; Plutarch, in Parallel Lives, sought to study the great leaders of antiquity and his present, but from a morally instructive5 perspective as much as a historical one. For a charismatic leader inevitably amasses followers and admirers, many of whom make as great or even greater impact on the course of history, forming communities and movements that span centuries. Their study becomes mandatory for those aspire to similar greatness. But not all leaders have sacred connotations to their personality, nor do they all equally elicit a delirious religious fervour in their followers.

The fervour that moves the body of the modern world is categorically political in nature; demagogues, de-facto tyrants and technocrats are the object of unrelenting populist zeal, both for and against. Transiently charismatic leaders are presented one after another at election cycles and geopolitical crises, as the antidote to, or cause of, the pressing existential concerns of the general public. This public will then rally around these figureheads and create communities of acolytes that will campaign and proselytise, no doubt motivated by hope for a Golden Age. This sentiment is not so different to the perspectives of Devi, and leaves onlookers just as incredulous. The incredulity is, to be direct, of incomprehension of the psychology of influence that people are individually and collectively susceptible to. This incomprehension leads them to loudly wonder at the ease with which the tides of favour turn for and against their political leaders, and by extension, their own hope for a brighter future for themselves and their loved ones. The fortunes of their ideological leaders are intrinsically tied to their own fate and the fate of their community, or so they feel.

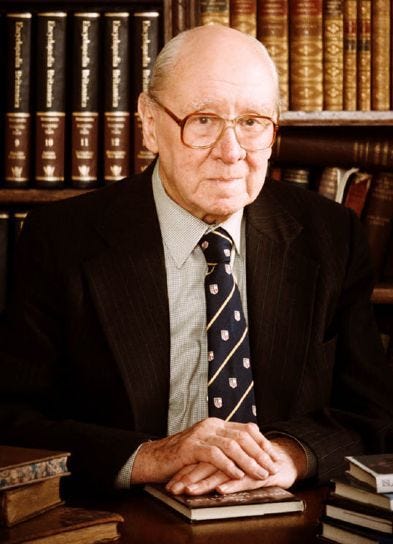

It is interesting that in their study of charismatic leaders, both Devi and Carlyle offer perspectives on the Prophet Muhammad; Devi identifies him, alongside Adolf Hitler, as a man against Time and a representation of the Lightning and the Sun that sought to strive against the decline of the Kali Yuga6. Carlyle describes him in less heterodox terms as the archetypal Hero as Prophet7 and considers him to be a great leader and reformer of a divinely inspired order. It is around the succession to Prophet Muhammad that Reverend W. Montgomery Watt (1909-2006), Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies at the University of Edinburgh, formulated his dynamic idea of Charismatic Leaders and Charismatic Communities. He sought to understand the theological crises in early Islam as analogues to historic and contemporary tensions within Christianity and the wider world, as well as to understand the psychology of devotion, as exemplified above in the impassioned rhetoric of Devi and those like her.

In Islamic Philosophy and Theology8, Watt delineates the sectarian tensions in the Ummayad Caliphate following the passing of the Prophet and how differences in group psychologies contributed to the formation of the charismatic leaders of the Shi’ites and the charismatic community of the Kharijites. The succession of leadership after the Prophet was a complicated affair, a time of psychological tumult for the nomadic and cosmopolitan Arab alike; the unconscious disposition of the people dictated their response to this uncertainty. Watt hypothesised that because the aristocratic South Arabian tribes were embedded in a tradition of civilisation a thousand years old with a succession of divine and semi-divine kings, in times of crisis they unconsciously looked towards charismatic leaders of this type. In contrast, the North Arabian tribes, who were nomadic and embedded in no such tradition, independently formed democratic communities with the belief that excellence was within the prestige of the family, clan and tribe; in times of crisis, their unconscious sought to recreate these charismatic communities with a clearly defined in-group and out-group.

Watt clarifies9 that his use of charisma and charismata is in a sociological sense rather than a religious one10; the prerequisite of a charismatic leader is the guarantee of salvation through allegiance and in the charismatic community it is salvation through participation. Those that fall outside this sphere are heretics and apostates, and depending on the extremity of interpretation, fit to be put to death. Watt recognises that the demarcation is not always clear, for a charismatic community may spring from a charismatic leader, or vice versa. For the Shi’ites, the charismata of the Prophet was transmitted to his family11; first through his cousin Ali ‘ibn Talib and his sons, and then followed by succession of divinely guided Imams that wield total spiritual and political authority. Thus the Shi’ites opposed the Umayyad caliphate on the basis that the successors of the Prophet were from his companions rather than his divinely guided blood. The Kharijites, on the other hand, believed that the increasingly affluent caliphate at the head of a rapidly expanding empire, no longer represented the values of the Quran and so they “with a fair measure of logic, worked out the Kharijite position to an extreme conclusion”. This conclusion was that both the authorities, who did not follow their interpretation of the Quran, and those that did not fight with them against the authorities, were outsiders that could be killed as a matter of duty. Thus salvation only lay within participation in the charismatic community, with deviations punishable by death. Watt points out that these extreme view points generated much theological discussion and eventually cemented the foundations of the moderate general religious movement which ultimately resulted in the Sunni orthodoxy as we know it today.

Watt does briefly consider Christianity, which also has a merging of the two concepts into a synthesis with its own particular weighting depending on the sect. The Roman Catholic Church recognises the charismata of Christ, but also has charismatic leaders in the form of the clergy and the Pope, who are in turn balanced by the Doctrine of the Church12 which establishes a charismatic community. He considers the Eastern Orthodox Church to be the best embodiment the charismatic community, though not implying that their views share the extreme nature of the Kharijites.

Watt refers to the deep resonant appeal of these two conceptions of leaders and communities as being a dynamic idea that all men are unconsciously13 inclined towards; indeed, though not indisputable nor universally applicable, it helps to frame the zealotry and polarisation of much current and historic political discussion. Many, like Devi, psychologically require an object of purely devotional leadership above all else, but today the salvation that is offered is of a comparatively material nature, be it economic security, reinstatement of normalcy14 or a brighter future for kin and countrymen, to name a few. Though divinity is not ascribed to modern leaders as a general rule, they nonetheless find themselves attributed supra human access to occulted planes of knowledge or insight, particularly in relation to the surreptitious workings of political machinery. Allegiance to the leader is often commitment enough, resulting in a potentially less exclusionary community more willing to tolerate any deviations in doctrine amongst its followers. Furthermore, there is far more tolerance for moral lapses, and far less demand of perfection, in the leader as compared to before, something Devi would attribute as a sign of the times. Those that are drawn towards the dynamic idea of a politically charismatic community find meaning, safety and hope within the participation of this community. However, much like the Kharijites, participation entails complete adherence a very well defined set of precepts, any perceived breach of which entails immediate expulsion and defamation. Though the in-group provides psychological stability amidst fear and insecurity, any consensus of application of political doctrine is ephemeral at best, leading to in-fighting and splintering off into more moderate or extreme communities.

Watt and Carlyle take a view of matters on a large historical scale, and Devi on an even larger cosmic scale. However one can view microcosms of Watt’s dynamic idea springing up all around them; online communities, for instance, create unifying charismatic leaders and lead to the formation of exclusionary communities and vice versa15. One quickly identifies those that are inclined towards salvation from participation in a community and those that wish to be led to salvation by an irreproachable and revolutionary individual, a particularly important skill in an increasingly globalised world prone to a dehumanising othering. More importantly, and selfishly perhaps, it prompts us to consider the ways in which we ourselves are inclined to think, reflecting in particular in the weaknesses and oversights in our structure of thought that lead to profound error. It is hoped that keeping these inclinations in mind balances the temperament and cools the passions, allowing the spirit and the intellect the freedom to engage with fractious matters. Perhaps it could help the incredulous to understand Devi, and those like Devi to conciliate with the incredulous. Perhaps not.

Manifesting, according to Devi, in the in Time figure of Genghis Khan; His destructiveness was the passionless destructiveness of Mahakala, all-devouring Time.

The Sun manifests as Akhenaton, who Devi states as being above Time and wishing to transcend the decline with the affirmation of Light and non-violence.

Arjuna, whenever righteousness is on the decline, unrighteousness is in the ascendant, then I body Myself forth. For the protection of the virtuous, for the extirpation of evil-doers, and for establishing Dharma on a firm footing, I manifest Myself from age to age - Bhagavad Gita

Carlyle gives the example of Napoleon as a Hero as King therefore it would make conventional sense to include Hitler in this category, both being controversial leaders that have changed the course of history. Ardent supporters of Hitler may have considered him a Hero as Prophet, the example of which Carlyle gives us the Prophet Muhammad. Other than Devi, few would consider Adolf Hitler a Hero as Divinity, a designation Carlyle reserved for pagan divinities and old gods.

Plutarch saw the virtue and moral integrity of leaders in decline, even among his Roman contemporaries. Roman Lives, Robin Waterfield’s dry but functional translation of a select few of Plutarch's histories, shows a moral decline even within a few decades of Roman leadership.

The fourth, final and most dissolute age in the Manvantara cycle.

The word this man spoke has been the life-guidance now of one hundred and eighty millions of men these twelve hundred years. These hundred and eighty millions were made by God as well as we. A greater number of God's creatures believe in Mahomet's word at this hour than in any other word whatever. Are we to suppose that it was a miserable piece of spiritual legerdemain, this which so many creatures of the Almighty have lived by and died by? I, for my part, cannot form any such supposition. I will believe most things sooner than that. One would be entirely at a loss what to think. of this world at all, if quackery so grew and were sanctioned here. Alas, such theories are very lamentable. If we would attain to knowledge of anything in God's true Creation, let us disbelieve them wholly! They are the product of an Age of Scepticism; indicate the saddest spiritual paralysis, and mere death-life of the souls of men: more godless theory, I think, was never promulgated in this Earth. A false man found a religion? Why, a false man cannot build a brick house! If he do not know and follow truly the properties of mortar, burnt clay and what else he works in, it is no house that he makes, but a rubbish-heap. It will not stand for twelve centuries, to lodge a hundred and eighty millions; it will fall straightway. A man must conform himself to Nature's laws, be verily in communion with Nature and the truth of things, or Nature will answer him, No, not at all! - Thomas Carlyle, Lecture II, On Heroes, Hero Worship & The Heroic in History (1840).

Published in 1962.

In his lecture The Conception of Charismatic Communities in Islam, 1960

Referring to the Christian use of χάρισμα; the gift of Grace from the Holy Spirit.

The Ahl-al-Bayt أَهْل البَيْت

Extra ecclesiam nulla salus

That is, related to Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious but without the metaphysical assumptions.

Warren G. Harding’s neologism; not nostrums, but normalcy

There is much more that could be said on this, were it within the scope of the essay. Cults of personality develop quickly and dissipate just as quick in the digital sphere, possibly because both the personalities and their admirers ignore the sage advice of never meeting one’s heroes. Intimate unbridled access to these all-too-human individuals inevitably results in disappointment, which then seeks to distract itself with the novelty of attachment to a new personality.